At the Working Group on Article 8(j) and related provisions in Geneva, members of the Transformative Pathways project held a side event to highlight the work Indigenous Peoples are doing to monitor their cultural and biological diversity.

On the 14th of November 2023, five representatives of the Transformative Pathways consortium gave presentations on the importance of community monitoring of land, biodiversity and traditional knowledge, demonstrating how mapping and monitoring can be vital tools, building on indigenous knowledge, for Indigenous Peoples to advocate for their rights and for the recognition of their contributions to biodiversity conservation and sustainable use.

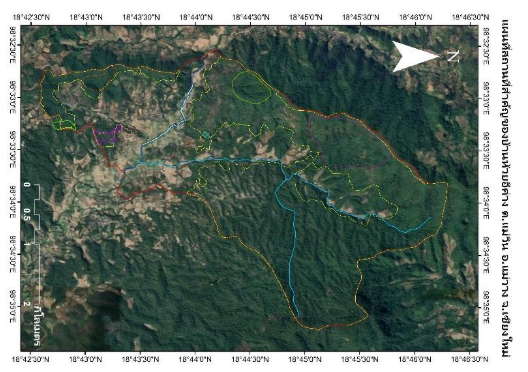

One of the key themes covered in the event was using tools to monitor the status of their land, including how it is used by communities and what plants and animals are found there. Fred Kibelio, from the Chepkitale Indigenous Peoples Development Project (CIPDP), Kenya, highlighted that monitoring community land is a practice that has been ongoing for centuries.

“Monitoring is not new to these communities,” Kibelio said. “It is not something that we are just beginning to do. It has always been there, but most of the information has been kept orally.”

New technology, such as Mapeo (a mapping tool that can be used on a smartphone by community members) provides communities with the technology to acquire and document stronger evidence of community land use through map data gathering. The communities – who own this data – can then present it to local and national authorities in support of their land and resource rights, and to engage in relevant conservation and land policies and laws.

“We are going to use technology to strengthen Indigenous knowledge,” Kibelio said. “[…] Our elders were happy to see that the Indigenous knowledge they already have can now be reinforced using these scientific methods.”

Type: Blog

Region: Global

Theme: Community-led conservation; International Processes; Land and resource rights; Sustainable Livelihoods; Traditional and local knowledge

Partner: Indigenous Information Network (IIN); Forest Peoples Programme (FPP), UNEP-WCMC, CHIRAPAQ, Chepkitale Indigenous People Development Project (CIPDP) and IMPECT

Mee Nittaya, Director of the Inter Mountain Peoples Education and Culture in Thailand (IMPECT) explains how mapping is used in communities during a Transformative Pathways side event at WG8(j) in Geneva, November 2023. Credit: Gordon John Thomas

Thai partner Mee Nittaya, director of the Inter Mountain Peoples Education and Culture in Thailand (IMPECT) agreed that community mapping is a vital tool. In Thailand, a lack of secure land tenure for Indigenous communities means the government and private companies can promote the growth of cash crops on their land, which in many cases negatively impact both biodiversity and communities’ livelihoods. To help combat this, community maps are extremely helpful, but they also need to be created in conjunction with the authorities.

“You need to collaborate with local authorities [in Thailand],” she said. “If you work just with the communities, the map might not be accepted by the local authorities, so it’s important to bring them in from the beginning.”

In Kenya, the Indigenous Information Network (IIN) has created Resource Centres where communities can meet, and they have become a key space for facilitating intergenerational transmission of traditional knowledge and skills. Daisy Chepkopus of IIN, explained that the communities have been training themselves to use new monitoring tools and to effectively engage with local and national authorities to strengthen their rights.

“We organise trainings and workshops involving Indigenous youth, women, elders and local officials,” said Daisy. “We make sure that the officials speak the local language.”

“Through the training at the Resource Centres, the youth themselves are taking the initiative to restore the land,” she added.

Tarcila Rivera Zea speaks about traditional knowledge and community monitoring at a Transformative Pathways side event at WG8(j) in Geneva, November 2023. Credit: Gordon John Thomas

Tarcila Rivera Zea, from CHIRAPAQ, Peru, explained that through creating dialogues between Indigenous Peoples from the Amazon and the Andes regions, communities shared their experiences on community monitoring as a tool to help adapt to climate change.

“An Indigenous women, through observation and reflection alone, can monitor the changes in her environment,” she said. “As the climate changes, the women changed the type of potatoes they were growing so they didn’t get eaten by worms who had come up from lower altitudes.”

The event was also attended by one of the global partners of the Transformative Pathways project, UNEP-WCMC, represented by Katherine Despot-Belmonte, the team at UNEP-WCMC are working to develop an indicator methodology related to the full, effective, equitable and gender responsive participation and representation of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in biodiversity decision-making to measure progress towards Target 22 of the GBF.

“As we have seen, Indigenous Peoples’ traditional knowledge and governance systems are powerful, but unfortunately when it comes to decisions made at the national level, they don’t always have a seat at the table” Katherine said.

“Our hope is that government representatives involved in the implementation of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework will use the indicator methodology to measure progress towards Target 22, and report on progress in their national reports” she said.

The Transformative Pathways project is a joint initiative led by Indigenous organisations in four countries across Asia, Africa, and the Americas, and supported by a network of global partners.

The project directly supports collective actions towards self-determined land and resource governance, biodiversity conservation and sustainable livelihoods.

To find out more about the work the Transformative Pathways project is doing on mapping, monitoring and engagement in national and international biodiversity processes, visit the Transformative Pathways website and sign up for the newsletter for the latest updates.