By Jacqueline Cariño, Partners for Indigenous Knowledge Philippines (PIKP)

At the heart of Baguio City is a remaining not-so-green space located between the Baguio Orchidarium and the Children’s Park. You enter through a side street beside the Rose Garden where the bicycles-for-hire are found, until you reach a wide-open grassland, with a small thatched-roof structure by the side and a stage at the center, surrounded by trees and vegetable gardens. This lot tucked into a corner of Burnham Park is what is now known as the Ibaloy Heritage Garden.

The Ibaloy Heritage Garden has a long and rich history tracing back to pre-colonial times. Before the coming of the American colonizers in the 1900s, the space was known by the residents as Apni, a pastureland where herds of cattle grazed and drank water in the nearby natural creek and watering hole called Miñac (now the famous Burnham Lake).i The area was part of the ancestral land of Ibaloy leader Mateo Cariño and his wife Bayosa Ortega. Thereabouts was the site of the couple’s original family residence, where they lived with their 9 children.

As history would have it, this area was taken over by the American colonial government for government purposes. ACT No. 636, enacted by the Philippine Commission on February 11, 1903, “reserved for Government purposes, exempt from settlement and claim: That parcel or tract of land in the form of a circle with its center in the house occupied by Mateo Cariño at Baguio, and with a radius of one kilometer.” Thus, all the land within a 1-kilometer radius from the residence of Mateo Cariño, was reserved and declared as public land for the colonial government’s use. Architect Daniel Burnham designed a plan to build Baguio as a garden city and summer capital of the Philippines. Large tracts of land were expropriated by the American government as institutional lands. Thus started the rapid development and urbanization of Baguio City. Throughout the 20th century, Baguio City rapidly grew into an educational, tourism, commercial, and government center of the Cordillera region. This process eventually led to the dislocation, minoritization and marginalization of the original Ibaloy families from the ancestral lands they once owned.

Type: Blog

Region: Asia

Country: Philippines

Theme: Community-led conservation and Traditional and local knowledge

Partner: Partners for Indigenous Knowledge Philippines (PIKP)

Photo: North Star Magazine

Fast forward to 2009: Baguio had become a highly urbanized, multi-cultural, and bustling city where the Ibaloys were now a minority population. The Ibaloys started to feel the lack of opportunities to come together as a community to continue their cultural practices. Cañao (ritual feasts), which were opportunities to gather, socialize, practice, learn and transmit their traditional Ibaloy culture, were still held, but rarely and in a scaled-down manner. Dwindling resources constrained the scattered Ibaloy families from performing foregone celebratory feasts of prestige. It was increasingly difficult to muster the resources needed to butcher the prescribed number of pigs and cows as ritual offerings to the ancestors, and to feed the whole community. Close cultural ties and traditional practices were on the downtrend. It was an expressed wish among the Ibaloys at that time, that they be given more opportunities to unite, reminisce, tell stories, chant the ba-diw, dance the tayao, play the kalsa and solibao, and teach their children and grandchildren about the traditional Ibaloy practices and values of solidarity and mutual support.

This situation motivated some Ibaloy leaders, led by respected Ibaloy elder and journalist Cecile Afable, to lobby the City government to recognize the important role and contribution of the Ibaloy in the development of the city. They sought to set aside a time and space for Ibaloys to gather, rekindle ties and revitalize their cultural identity. Their persistent lobby campaign was successful and resulted in the passing of 2 resolutions by the Baguio City Council.

Baguio City Council Resolution No. 395, S. 2009 declared February 23 of every year as Ibaloy day. It commemorates the day when the US Supreme Court recognized Mateo Cariño’s struggle for a Native Title, as well as to recognize the original inhabitants of Baguio City.

Baguio City resolution No. 182, S. 2010 designated the area between the Burnham orchidarium and the Children’s playground as the site for the Mateo Cariño monument and as the Ibaloy Heritage Garden. This allowed the local government, concerned government authorities, and the Ibaloy people to develop the area to sustain its status as a heritage garden.

Photo: North Star Magazine

And that is how the Ibaloy Heritage Garden came to be.

The 1st Ibaloy Day on February 23, 2010 was a groundbreaking and happy event for the Ibaloys of Baguio. “Clans and individuals donated ceremonial pigs that were butchered and cooked in the traditional style. Demshang, kintoman, ava, dukto and tapey were passed around to feed the crowd, composed of old and young Ibalois coming in their kambal, devit or shenget, who had gathered for the occasion. Ibalois beat the solibao, tiktik and kalsa and danced the tayao and bendian. Elders took turns telling stories and chanting the ba-diw. The different clans planted pine tree seedlings around the park, which they intend to care for until these grow into tall pine trees symbolizing the continuity of their clan. A time capsule was buried in the park led by the Ibaloi elders to mark the beginning of the development of the area as an Ibaloi heritage site. A Handy Guidebook to the Ibaloi Language was launched and distributed to the Ibaloi clans present to encourage them to speak the language and teach it to the younger generation. A map of Baguio was put up containing the original Ibaloi place names and the new place names in the city for people to correct and add on what they know. The atmosphere of the affair was celebratory and felt just like the traditional kedot, with the program and other various activities going on and everyone just having a good time. It was a day to remember as the Baguio Ibalois, even then, already looked forward to celebrating the next Ibaloi Days in the years to come.”

Today, the Ibaloy Heritage Garden has become the site of the annual celebration of Ibaloy Day on February 23, through the organization and management of Onjon ne Ivadoy. Development of the Ibaloy Heritage Garden continued with the building of the Avong, through aduyon or collective labor and cooperation. The Avong now serves as a communal place to gather, cook, eat, drink, meet, learn, tell stories, and spend time together with other Ibaloys and friends. It has since been rebuilt and expanded to serve as a functional space for holding various and numerous events, not only for the Ibaloys but for the wider Baguio community.

A major feature of the Ibaloy Heritage garden is the Ba-ëng or traditional Ibaloy home garden.

Vicky Macay relates, “In the Ibaloy Heritage Garden, we keep a ba-ëng or a home garden. For us Ibaloys, growing food in the ba-ëng is part of our culture. We started the ba-ëng here just for fun. We planted coffee and seeds given by members. Since then, we added more plants like saba and vegetables. … We got young ones to help us in maintaining the ba-ëng. Every Saturday there are activities where we teach children or anyone who wants to learn about ba-ëng.”

Partners for Indigenous Knowledge Philippines (PIKP) supported the maintenance of the ba-ëng in front of and around the Avong during the pandemic to develop it as a learning site for the transmission of indigenous knowledge on home gardening. Indigenous knowledge on home gardening was documented and published in a book “Welcome to our Ba-ëng” by Ibaloy elder Vicky Macay. Educational videos, a training module, learning visits by students, and maintenance of the ba-ëng as a source of food were conducted, including setting up a stand for the water tank to facilitate watering of the plants.

Photo: North Star Magazine

The Ibaloy Heritage Garden has since become a valuable space for numerous activities aimed at revitalizing Ibaloy culture. The Ibaloy Festival held during Indigenous Peoples Month in October 2023 served as a school of living traditions, where language, rituals, medicinal plants, cooking, dance, and music were taught. Ibaloy clans of Baguio and Benguet gathered to trace their genealogy, set up booths and exhibits, which also served as clan reunions and opportunities to perform traditional rituals that they had been unable to perform before.

The Ibaloy Heritage Garden has now grown into a cultural center for other indigenous groups and organizations in Baguio as well, such as Kalinga Day, Ifugao Day, and the Cordillera Gong Festival. It serves as a venue for other public events like press conferences, art exhibits, concerts, beauty pageants, even parties. It has also been used for commercial purposes such as trade fairs, a parking lot, landscaping competitions and flower stalls, and a coffee shop. This latest development towards commercialization has given rise to questions on the use of the space for business, since public parks and spaces are supposedly “beyond the commerce of man.”

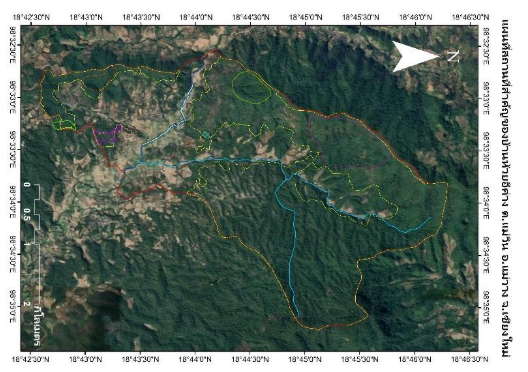

Plans for the further development of the Ibaloy Heritage Garden. In 2019, City Mayor Benjamin Magalong created a Technical Working Group to formulate a Master Plan for Burnham Park reservation. It was agreed that the design for the development of the Ibaloy Heritage Garden would be done in keeping with Resolution No. 182, S. 2010, and by the Ibaloys themselves. After a series of consultations, a Site Development Plan for the Ibaloy Heritage Garden and Mateo Cariño Monument was prepared by Ibaloy Architect Keenan Camilo. The plan consisted of a monument, urban gardens, aspulan or gathering place, abong, a coffee garden, among other features. This plan was adopted by the City Council for incorporation into the Master Development Plan for Burnham Park Reservation on March 3, 2020. The Council further endorsed the plan to the City Environment and Parks Management Office (CEPMO) for their appropriate action.

Funds in the amount of PhP78 million have since been allotted by Senator Robin Padilla for the City to proceed with the development of the Ibaloy Heritage Garden. The CEPMO made some changes in the site development plan, though it is not so clear how much the new plan has deviated from the original design prepared by Architect Camilo and approved by the City Council. This is something that we should be watchful of. The bidding out of the project to contractors is scheduled this March 2024, to start the development work.

Significance of the Ibaloy Heritage Garden in a Sustainable Baguio City. The development of the Ibaloy Heritage Garden should be true to its original purpose as a center for the revitalization of Ibaloy indigenous culture and identity. Now more than ever, amid a city bursting beyond its seams, a space is needed where the Ibaloys can feel free to breath and find communion with kindred souls. The Ibaloy Heritage Garden can be likened to the bintuan, a traditional hearth in the kitchen where the family gathers to share food, drink, and stories around a fire. It is here where elders recall, share and rekindle indigenous values of caring for the family, their community, and the environment. The Ibaloy Heritage Garden serves as a hub for various initiatives that strengthen and promote indigenous knowledge, values, and practices, while transmitting these to the youth and generations to come. It bustles as a hive of numerous events and activities that bring together various indigenous groups, organizations, and other sectors of the city in the common desire for unity and solidarity. It serves to bring the Ibaloy people back from the margins to the center of Baguio City life. It could and should continue to be a model of regenerative development for a sustainable Baguio.

As Manang Vicky Macay says, “The Ibaloy community is blessed to have the Ibaloy Heritage Garden where we can gather together to tell stories, reminisce, and teach our children and grandchildren about the traditional Ibaloy practices and values of solidarity and mutual support…. We continue to look for opportunities to transmit our knowledge to the younger generations. This is our way of helping them carry on the culture and values taught by our ancestors. Today, there is now a growing effort to rekindle Ibaloy culture and identity, learn the language, and find ways to get the young people involved in learning and practicing the Ibaloy culture and tradition.”