Phoebe Ndiema and Elijah Kitelo, both biodiversity fellows at the Interdisciplinary Centre of Conservation Science (ICCS) at the University of Oxford, led a hybrid workshop on biodiversity monitoring protocols on the 7th June, 2023. Attended by Oxford academics from a wide variety of expertises – from technical mapping to ornithology – the workshop discussed how monitoring practices could support both indigenous land rights claims and the fine tuning of current community-led conservation practices.

“We want to monitor biodiversity to rejuvenate areas of tropical forest, and to ensure that we utilise our traditional knowledge of conservation,” said Phoebe in her presentation.

Phoebe and Elijah are from an indigenous Ogiek community in Mount Elgon, Kenya, that have been conserving and sustainably using their ancestral land for centuries. However, they are facing multiple threats to their way of life, including violent evictions by the government in order to create national parks, illegal logging, poaching and the encroachment of small-scale farming.

“We want our rights to be recognised,” said Elijah during the workshop. “We don’t want to get kicked out. We want to get land tenure, and then work together with the authorities to help conserve the land.”

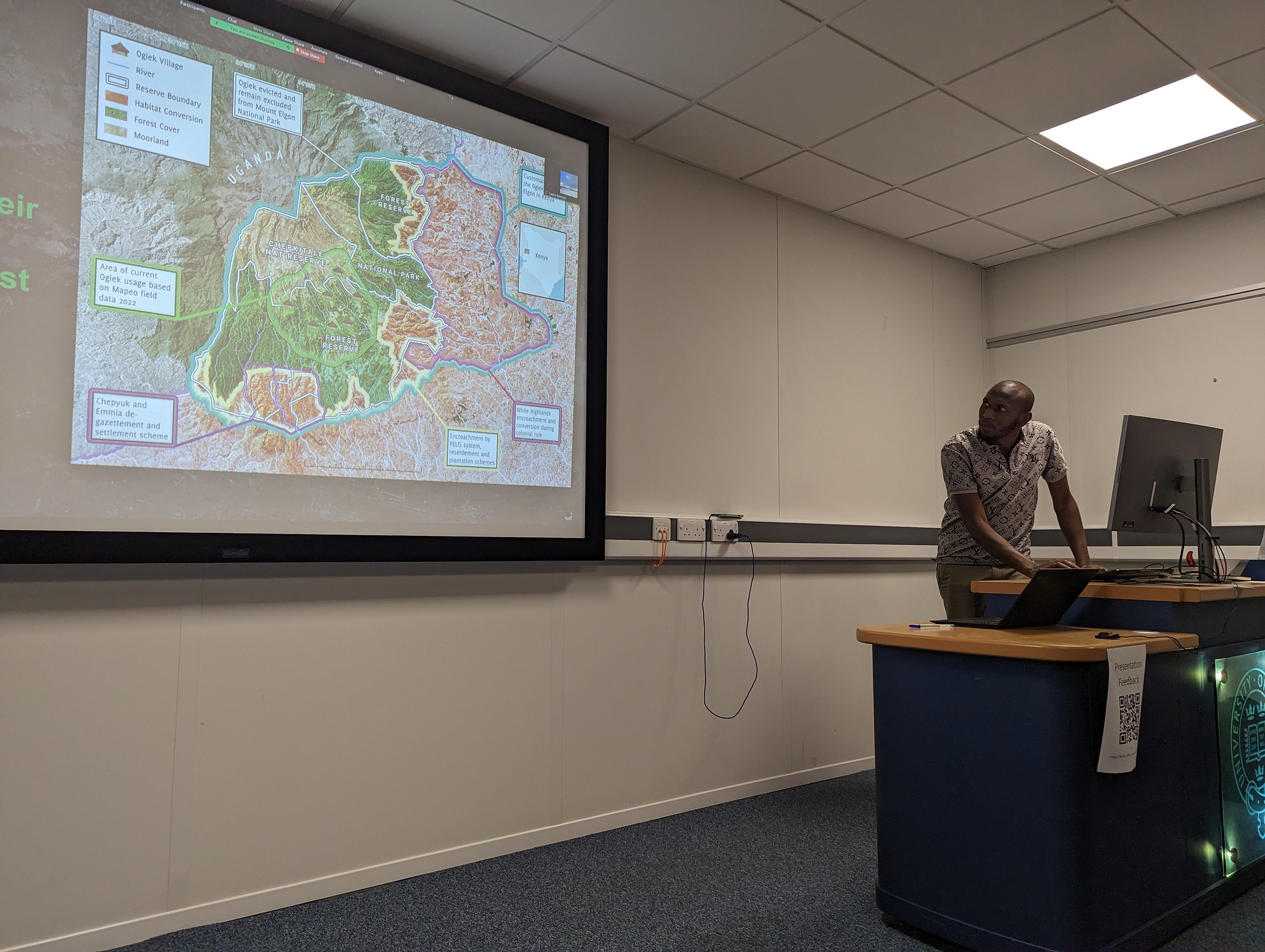

In their respective presentations on the current land and biodiversity situation in Mount Elgon (from maps created using community-gathered data), it was clear that the areas not cared for by the Ogiek people were undergoing much faster biodiversity loss.

Type: Article

Region: Africa

Country: Kenya

Theme: Community-led conservation; Sustainable livelihoods; Traditional and local knowledge.

Partners: Chepkitale Indigenous Peoples Development Project (CIPDP), Interdisciplinary Centre of Conservation Science (ICCS)

”“We want to demonstrate to the environmental policy makers both at national and international level that Indigenous people; Ogiek in this case, can coexist with nature without harming it” - Phoebe Ndiema, CIPDP

Elijah Kitelo (CIPDP, Kenya) at the University of Oxford delivering a workshop on biodiversity monitoring protocols.

Phoebe and Elijah work with a community-led organisation called Chepkitale Indigenous Peoples Development Project (CIPDP), which is currently involved in a court case to get official land tenure of their land. To do this effectively, however, they need to prove that the Ogiek people have inhabited the area for over 100 years, and that their presence on the land is positive for biodiversity conservation.

To do this, they have been researching different methods of biodiversity monitoring and restoration practices, as well as accessing Oxford archives for maps created of their land in the 19th and 20th centuries.

“We want to monitor our species, to ensure that we restore biodiversity that used to be there but has been lost,” said Phoebe. “We want to show the world that indigenous knowledge can coexist with nature without harming it, so we are not evicted in the name of conservation.”

Phoebe Ndiema (CIPDP, Kenya ) and her group discuss biodiversity monitoring protocols

One of the key questions discussed at the workshop was how the CIPDP could use biodiversity monitoring techniques in order to present indisputable evidence of Ogiek customary care of the land. This would not only support their current land rights claims in court, but also be a step towards working together with current forestry authorities for conservation purposes.

As Tom Rowley, Community-based Mapping & Monitoring Officer at Forest Peoples Programme, said:

“What type and quality of evidence would be needed to change [current Kenyan] forest management policies? How can we achieve this in a way that doesn’t override indigenous wisdom or replace it with another value set?”

Group discussions highlighted various possible solutions, such as learning from previous successful land rights claims (Like the Ogiek peoples in September 2022), and using oral evidence, like stories from elders, to show changes in land use and examples of species degradation.

Many conversations discussed the importance of a mix of research methods, both those that reflect indigenous knowledge and other monitoring methods that are commonly used in ecological studies, as a way to gather evidence for community use and also ensure that it stood up to rigorous scrutiny in court. By training community members to gather evidence in line with international academic standards, they could then become experts in new data-gathering techniques.

Phoebe and Elijah will return to Mount Elgon, Kenya, on July 4th, with a member of the ICCS team, where they will work together with their community to develop community-led biodiversity monitoring practices.