Blog article by Susana Núñez Lendo

Janet Chemtai introduces herself: “I represent all the indigenous women across the mountain.” . The mountain is Mount Elgon, an extinct volcano on the border between Uganda and Kenya. She is an Ogiek leader, chairwoman of the Chepkitale Women Council, and has been repeatedly elected by a show of hands by the women of her community for several years.

Ever since colonial times, the Ogiek have faced efforts to expel them from their ancestral forest, often under the guise of environmental protection. Janet recalls an episode in which the men of the community were shot at by forest authorities to forcibly remove them from their land; an extreme situation that pushed the women to take a more active role in the defence of the community.

“I think that for the first time, we women in the community realised that when a man can do something, a woman can do it too. There’s a saying: What a man can do, a woman can do better!” she says with humility, bursting into laughter.

The pretext that the Ogiek are degrading the lands is sometimes accompanied by the accusation that their presence affects wildlife. Janet sketches out a peaceful coexistence:

“In this community, we have domestic animals like cows, and wild animals. Sometimes our animals get close to the wild ones, but we respect them. Also, we women carry out our activities in specific areas, not just anywhere: we’re aware that we could harm our environment.”

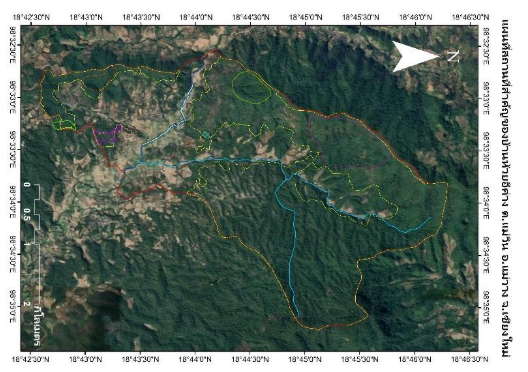

Mount Elgon seen from Chepkitale, Bungoma County, Kenya. Photo Credits: Susana Núñez Lendo/FPP

“Just moments ago, about forty of us arrived at Chepkitale; we have just finished the welcome dance.”

Her village is hosting the first Africa Regional Extension Workshop, a horizontal learning event among African Indigenous Peoples and local communities, held within the framework of the Transformative Pathways project.

It is a great opportunity to talk about the women-led basket weaving art of the Ogiek people.

“Since time immemorial, we’ve been using these baskets for fetching our food. Now I am going to put my bit in it, look!”.

Each woman puts ‘her bit’ in the basket, a small handful of straw, to symbolize the contribution each member makes to the community. Photo Credits: Susana Núñez Lendo/FPP

The baskets taken in the photo are made from bamboo, gathered from the edge of a bamboo forest where majestic elephants graze, not far from the village.

“We have always used the baskets to carry goods to the market, and we trade them in the market, but we have now also started using them as dustbins. This way, we avoid using plastic bags or containers that pollute the village. […] In this community, we have proven that we know better than anyone else how to conserve and progress. We have inherited this environment, and we protect it. Our men collect honey; we, with our cows, get enough milk, sell it, earn money, and send our children to school.”

When the Ogiek have been forcibly evicted, the forest and the elephants are no longer protected by them: instead the forest is destroyed by charcoal burning, and felling to make fields, and the elephants are under threat from poachers and the destruction of their habitats.

During out visit, the women wove baskets together as a family on their ancestral lands, sharing stories, learning together, laughing, living in harmony with the land.

Janet’s words are testament to how their traditional livelihoods allow the community to protect their ancestral land, as well as maintaining their traditional knowledge while adapting to a changing world. This is a stark contrast to those who are trying to gain control over the land, destroying it in their quest to profit from it.

The Ogiek, as hunter-gatherers, use baskets made from plants to collect fruits, berries, and more. Janet Chemtai symbolically adds her share to the bamboo basket, representing her people’s gathering tradition. Photo Credits: Susana Núñez Lendo/FPP

Type: Blog

Region: Africa

Country: Kenya

Theme: Community-led conservation; Sustainable livelihoods; Traditional and local knowledge

Partner: Forest Peoples Programme; Chepkitale Indigenous Peoples Development Programme (CIPDP)